This post was sparked by a recent advocacy project — one that’s deeply invested in the unsugared realities of chronic illness. With steroids keeping my brain whirling last night, a flood of thoughts came rushing in. I’ve lived with this disease since early childhood — nearly 70 years — and I realized how much remains unseen, and how much still needs to be said.

Here’s what they dont see…

People see me walking, traveling, staying fit — and assume I’m healthy. They even say “Hey, you look great for your age”. But what they don’t see is the daily grind of symptoms, the flare-ups every couple of months, the ER Resusciation Room, the Hospital admissions, the ventilator episodes, the multi-day bouts of ICU induced Delirium and the long, grueling recoveries that follow. What they don’t see is the mental toll of steroids, the insomnia, the mood swings, the depression. And what they often forget — even the medical folks — is that extremely severe asthma is a different animal altogether. It’s not just about wheezing or needing an inhaler occasionally, it’s about waking up gasping for air every single night and knowing that no matter how well you manage it, the disease is always there, lurking in the background. And there is no cure insight.

The Vicious Cycle and What Follows

The Vicious Cycle and What Follows Breathlessness is my baseline — not an occasional symptom, but a constant companion that varies in intensity throughout the day, often worsening at night.

When Breathing Becomes Conscious

When Breathing Becomes Conscious

I’m short of breath to some degree, 24/7. Not just during flares. Not just when I’m sick. Always. Sure, I get moments of relief—especially after a breathing treatment—sometimes for a few hours. But that’s the point: people with healthy lungs don’t think about their breathing. It’s automatic. Background noise. You take it for granted.

With chronic lung disease, breathing is never automatic. It’s front and center. You’re constantly sensing, comparing, evaluating: Is this better or worse than yesterday? Is this tightness normal? Am I just tired, or is something brewing? Sometimes I don’t even realize my “not-so-good” breathing is getting worse until I’m in trouble. They call that “poor perception.” But I’m a strange mix—both an over-perceiver and a poor one. Hyper-aware of every nuance, yet sometimes blind to the slow decline.

It’s exhausting. Not just physically, but mentally. Because when breathing becomes conscious, it becomes a burden. And that burden never really lifts.

This isn’t just “bad asthma.” My lung function hovers around 28–30% of normal, a result of irreversible airway remodeling from decades of exacerbations and the very drugs used to treat them. Once that damage occurs, there’s no going back — the goal becomes preventing further decline. That means every flare-up hits harder. Unlike most asthmatics who recover to near-normal lung function between attacks, I have no such reserve. When my breathing worsens, I’m already starting from a deficit, and the margin for error is razor-thin.

When I was younger, my exacerbations were acute and abrupt — triggered by allergens, infections, or exercise. But as my lung architecture changed, my airways became less “twitchy.” I had fewer spasms, but more air-trapping. Attacks now build slowly, sometimes over days or weeks, with a creeping inability to exhale. These brewing exacerbations may not seem as dramatic, but they’re often more dangerous. By the time breathing becomes noticeably difficult, it’s usually too late to self-treat. You need hospital-level intervention — or more accurately, hospital-level monitoring. Because while the drugs are familiar — steroids, bronchodilators, oxygen — the doses are massive, and the stakes are high. They monitor your blood gases, your vitals, and if needed, they support your breathing mechanically. And if you end up on a ventilator, it’s considered an NFA (near fatal attack). Each one increases your risk of another — or of not surviving the next.

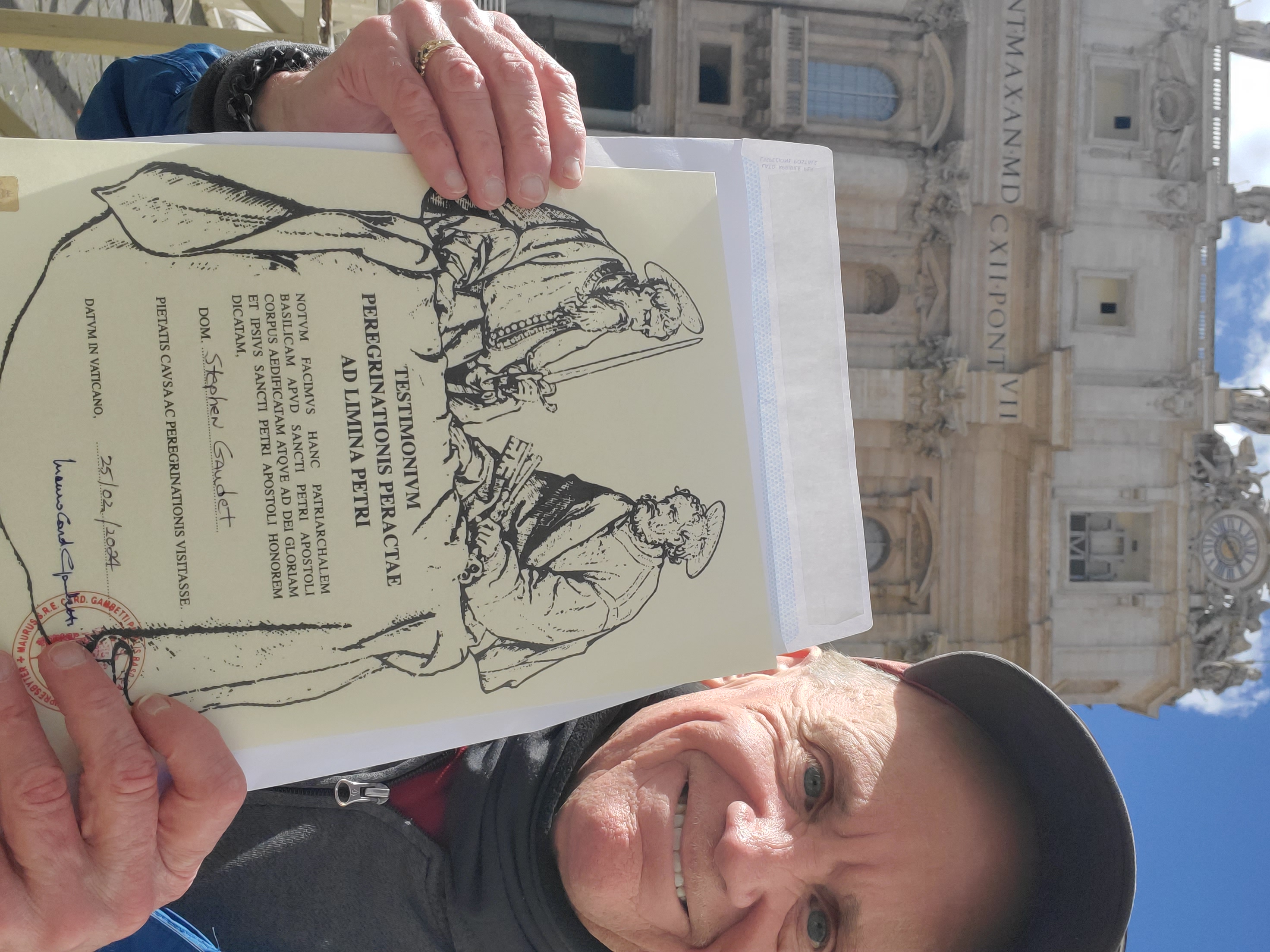

Living with It, Not as It. Despite everything, I’ve worked hard to create the best life I can for myself. Fitness plays a huge role — not just for lung function, but for mental clarity and emotional strength. I walk and I stay active because it’s the only way I know to push back against the disease.

But it’s not just about movement. Music, blogging, and trip planning have been my refuge. Each one gives me back something the disease tries to take away. Playing bass offers rhythm and control when my breathing feels chaotic. Blogging lets me document the truth—when something resonates, when a moment feels worth sharing, or when I think others might see themselves in my story. It’s not a business, it’s not a brand. It’s how I advocate, connect, and make the invisible visible. Trip planning gives me something to look forward to—a way to stay mobile and feed the part of me that’s always restless to explore. It’s not about proving anything. I just want to keep going. These aren’t just hobbies. They’re lifelines. They help me stay grounded, expressive, and connected — even when my lungs aren’t cooperating.

I don’t present as “sick” or “disabled,” and that’s intentional. I don’t think of myself as my disease. I’ve lived with it for decades, but I’ve never let it define me. People might see me and think I’m healthy — and in some ways, I am. But that appearance is the result of relentless effort, not luck. It’s the product of discipline, routine, and a refusal to let asthma dictate the terms of my life.

Asthma’s Bonus Gifts

As if living with chronic severe asthma weren’t enough, there’s a whole catalog of complications that come along for the ride — some caused by the disease itself, others by the treatments that keep you alive. I call them asthma add-ons — sarcastically, of course — because they feel like unwanted prizes for surviving this long.

Posterior Glottic Stenosis: Because Ive been intubated so many time (57 to be exact) I developed posterior glottic stenosis — a narrowing of the upper airway that makes breathing even harder. I’ve had seven dilation surgeries to reopen the space, and ironically, the procedure itself triggered my asthma on all but six occasions. It got so bad that my ENT started scheduling dilations while I was already on a ventilator for an asthma flare. How crazy is that?

Radial Artery Scarring: Decades of arterial blood gases (ABGs) and A-lines — I estimate around 200 — have left my radial arteries scarred to the point where my left one is completely occluded. It’s a permanent reminder of how invasive asthma management can be.

Vein Damage and Port Placement: Prednisone doesn’t play nice with veins. After years of use, mine became so stiff and inaccessible that I had to have a permanent port placed into the right side of my heart just to ensure reliable access. That was eight years ago, and it’s still in use.

Urinary Retention from inhaled medications: Some inhaler combinations, especially those containing anticholinergics like the medication in Spiriva, helped my breathing but caused urinary retention — a side effect that led to multiple follow-ups with a urologist. Eventually, I had to stop using them, which was unfortunate because they actually worked well for my lungs.

The Usual Suspects: Then there are the more “common” side effects: insomnia, severe muscle cramps, mood swings, fluid retention, and the ever-present mental fog from steroids. These are so routine they barely register anymore — but they still take a toll.

What I Wish People Understood:

Severe asthma isn’t just “bad asthma” — it’s a different disease entirely.

*Daily symptoms are the norm, not the exception.

*PTSD caused by ICU Delirium are real consequences of Severe exacerbations and NFAs

*Looking “well” doesn’t mean being well.

*Recovery is often harder than the attack itself.

Still here… still breathing — just not the way you think.

After seventy years of breathlessness, I’ve learned that survival isn’t the same as wellness. I’ve lived a full life, but not a day of it has been easy. The fact that I’m still here — still walking, still playing bass, still telling this story — is a testament to relentless effort, not luck. I’ve had to fight for every breath, every moment of clarity, every inch of autonomy.

I’ve been on Fasenra for nearly three years. It doesn’t make me feel better day to day. In fact, the shots often leave me feeling flu-like and sometimes worsen my breathing. But I haven’t been intubated in almost two years — a personal record. I can’t say for sure if the biologic is responsible, or if I’ve just become better at managing my disease. Maybe it’s both. Maybe it’s neither. I keep taking it, mostly to keep my doctors happy.

This is the reality of living with chronic severe asthma. It’s not just about managing symptoms — it’s about managing the fallout, the side effects, the complications, and the emotional toll. It’s about showing up every day, even when your lungs don’t want to. It’s about refusing to be defined by a disease that never really lets up.

The Daily Grind You Don’t See

Beyond the complications and the hospitalizations, there’s the mundane—but relentless—routine of severe asthma care. On a good day, I average 60 nebulizer treatments. That’s not a typo. Because MDI bronchodilators rarely cut it, I rely on budesonide and formoterol in the morning and evening, plus PRN albuterol around the clock. That adds up to a solid hour every day tethered to a machine, just to keep my airways open.

Then there’s the monitoring: blood pressure, SpO?, peak flows—twice daily, logged and tracked. And outside of the actual therapies, there’s the administrative grind. MyChart messages to doctors. Scheduling and attending medical visits, both online and in-person. Monthly lab work. Ordering medications by the boatload. It’s not dramatic, but it’s constant. Just another part of living with this disease.

I don’t look sick. I don’t act sick. But I live with a condition that has tried to take me out more times than I can count. And I’m still here. Still breathing, though labored at time, and Still telling the story most people never hear.